Are You Sure You’re NOT Infected with Malware?

Don’t Fall Victim to Malware or Ransomware Attacks!

Detect and remove malware, viruses, ransomware & other threats for FREE! Get Protected with SpyHunter.

Download SpyHunter (FREE Trial!)*Ransomware is a type of malware that generally prevents its victims from using their computer and accessing data, then demands some form of monetary ransom to allegedly restore access. Ransomware rose to prominence around 2005 and had another surge in popularity around 2013, when the infamous CryptoLocker variant affected half a million systems. Malware classified as ransomware became the predominant threat in the digital landscape in recent years, despite a gradual drop in the volume of infections and victims.

The common subdivision of ransomware is into two groups − encrypting or crypto ransomware and screen-locking or locker ransomware. The two groups differ dramatically in their way of preventing access to the system and the data on it.

Encrypting Ransomware

Encrypting ransomware is the much more common variant of the malware. On the most basic level, it uses mathematical encryption algorithms to scramble the data inside a victim’s files, leaving them inaccessible. The user is then presented with a ransom note, often dropped as a plain text file on the desktop and opened automatically. The ransom note contains the exact payment details the victim is expected to use to ransom out their data, as well as the technical details related to the exchange. The most common payment method is Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies as those are virtually impossible to trace.

In the most common case, ransomware uses a strong encryption algorithm that is either AES (Advanced Encryption Algorithm) – the U.S. government standard in encryption, or RSA (Rivest, Shamir, Adleman). It is possible to also use a combination of the two methods. Examples of hybrid encryption ransomwares are notirions names like WannaCry, Petya and its follow-up called NotPetya.

Encryption uses what is called a ‘key pair’ − two separate alphanumeric strings that are used for encrypting and decrypting the data. The public key is the string that will usually appear in the ransom note. The private key is commonly generated and immediately sent to a server operated by the cybercriminals. The decryption process requires the private key to be matched with its public pairing stored on the victim’s machine.

Over time, encrypting ransomware attempted many ways to store and distribute the key pairs. To circumvent the need for an active Internet connection at the time of encryption, cybercriminals resorted to a hybrid technique combining server and client (victim) asymmetric encryption, in conjunction with symmetric encryption. In this method, both the ransomware on the infected system and the server will generate their respective key pairs. This approach involves the encryption of one key string using another key string, which makes the whole process a lot more complicated and a lot more difficult to reverse-engineer and battle.

Notorious examples of encrypting ransomware include the CryptoLocker family, CryptoWall, TorrentLocker, as well as the later Locky and WannaCry ransomware threats.

Screen-Locking Ransomware

Locker ransomware is a far less destructive type of ransomware that restricts usage of the infected system by locking up the screen and displaying an alarming message. In the general case, screen-locking ransomware never bothers with encrypting the victim’s files and relies solely on scare tactics and sheer bullying to get its victims to pay the ransom. Common motifs encountered among screen locker ransomware strains are messages that the FBI or the police have found illegal materials on the victim’s system and that a fine should be paid to avoid prosecution.

Screen lockers tend to scare people into believing that the authorities discovered either illegal pornographic images on the victim’s computer, or large amounts of pirated digital media. The on-screen ransom demand is usually also much smaller than the sort of money crypto-ransomware demands. This is in part due to the fact that the claims screen-lockers make are so outlandish and absurd that the payment has to be made impulsively, before the victim has had time to assess the situation.

Obviously, the Federal government and the local police will never attempt to get in your home computer and lock it up, no matter how many mp3 files you may have on it. The notion that anyone can buy their way out of owning illegal adult imagery is also ludicrous. However, this vector of attack relies on scaring the victim enough to make the payment without thinking, acting out of irrational fear. This approach is just one of several social engineering attacks that cybercriminals resort to.

The fact that screen-locking ransomware does not encrypt files means more experienced users can manually get rid of the issue, use an anti-malware program to clean it or simply relocate the affected hard-drive to another system and clean and salvage the data there.

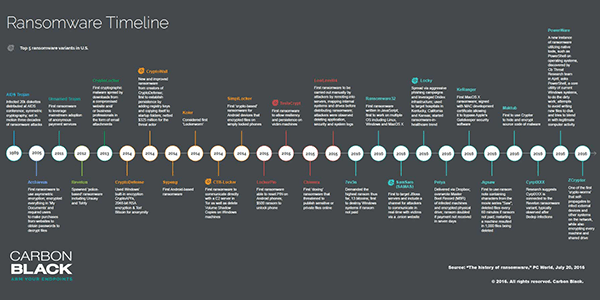

[click for larger image] Ransomware Timeline/Top Variants from 1989-2016 – Source: PC World/Carbon Black

Various families of ransomware use different methods of infiltration. Often samples within the same broader ransomware family use different approaches to infect their victims. However, there are a few methods that are prevalent in the ransomware landscape and can be singled out.

Malicious attachments in emails can contain a wide variety of payloads and ransomware is one of those. Despite what common sense might dictate, phishing remains a surprisingly effective infection vector even today. The attachments can have nearly any extension and needn’t be an executable file. This allows cybercriminals to use files resembling official documents, such as PDF and Word documents.

Phishing emails might also contain malicious links that point to malicious files that will download and deploy after a single click, which makes them particularly high-risk.

Another effective vector that bad actors use to spread ransomware are exploit kits. Code injections into compromised web pages, redirects to harmful sites and malicious banners are just a few of the components that can work together to deliver a ransomware payload to victims’ computers.

Ransomware hit what were arguably all-time peak levels in 2017. In that year, more than half of all worldwide malicious payloads were ransomware. Ransomware also proved to be a surprisingly effective malicious tool. Statistics for business entities show that over 70% of the companies that were targeted by ransomware actually did get infected and consequently suffered various degrees of losses and issues. A success rate that high shows that those businesses were, at large, not prepared to tackle the ransomware threat effectively – a mistake that was likely rectified after the attacks.

Despite the increase in ransomware infections over 2017, phishing emails carrying ransomware payloads were steadily declining. However, remote desktop protocol (RDP) rose dramatically, with over 60% of ransomware infections in 2017 being carried out through RDP.

Cybercriminals were also getting increasingly bolder and more confident with their ransom demands. In 2017, the average ransom demanded by the ransomware makers had gone to over $1,000 – a marked increase over the past years. Of course, that does not mean cybercriminals were more willing to deliver on their part of the supposed bargain. Even though some affected businesses chose to pay the ransom, the criminals never restored their data. It is hard to tell whether this was due to simple incompetence or because it never was the plan.

Over the following years ransomware attacks on large corporate entities and government institutions increased dramatically. One very prominent example was the attack on Norsk Hydro, who spent over $50 million in their efforts to recover from the LockerGoga ransomware.

A large number of United States government institutions including municipal networks were also targeted by ransomware, with varying degrees of success and causing different degrees of service disruption. The increasing popularity of attacks on institutions and businesses in the US led to the FBI issuing official ransomware prevention and response guidance.

A lot of intriguing and often alarming things took place in the field of ransomware attacks in 2019. Here are a few facts and statistics:

The biggest ransomware payout in 2019 was the $600,000 that Riviera Beach City, Florida chose to pay after a stray click on a phishing link led to what looked like another Ryuk infection. This is not the biggest ransomware payout of all time, though. The top spot is still occupied by a South Korean web hosting company who paid around $1 million back in 2017.

Of course, a lot of big businesses refuse to negotiate with hackers and choose to suffer massive losses rather than pay money to cyber criminal organizations. Again, Norsk Hydro who suffered $50 million in losses over a Ryuk are one very prominent example of a company who decided to roll with the punches and refused to pay.

Ransomware remains a very pertinent threat today and can target both corporations and home users.

Last updated: 2026-02-07